Syrup of frivolity to endure the genocide in the heels

By Iñaki Estívaliz

Photos by Alessia Maccioni, Marcos Méndez and Iñaki Estívaliz

The average Lebanese borrows money from family, friends and even the bank, if necessary, before missing out on a weekend party. This is assured to me by Ameed, the young concierge at my hotel in Beirut, whose eyes light up when he sees me leaving the elevator looking like I’m going out.

“Finally, Mr. Iñaki, you are going to get to know the real Lebanon, because here, where we don’t have outstanding athletes and our soccer team stinks, nothing happens -he makes a gesture with his shoulders, hands and face that means: apart of wars–, but we know how to have a good time.”

Beirut has not raised its head since the civil war of 1975-1990, which was followed by invasions of Palestine, Israel and Syria, social and economic crises and assassinations. All these hardships were always spurred by the Zionists, experts in destabilizing the region. Since 2022 there has been no president in Lebanon and the Iranian-funded Shiite group Hezbollah practically controls the country.

This chronicle is published shortly after one year of the incursion on October 7, 2023 of the Palestinian political and military group Hamas into territory occupied by Israel, which responded to the last phase of the genocide that the Zionists began in 1948 with the so-called by the natives Nakba (the great catastrophe).

If they had convinced us that Hamas was a terrorist group, Israel has ensured that we now see it as a front of resistance and national liberation.

More than 40,000 people, mainly children, have been annihilated, some two million Palestinians have been displaced and the Gaza Strip, the largest open-air prison in the world, has been devastated.

Despite these calamities, Beirut still retains much of that cosmopolitan splendor that has attracted travelers for millennia.

The day after my arrival in Lebanon, thousands of Lebanese Shiites in the south of the country said goodbye to Commander Hussein Ibrahim Kassab, leader of Radwan, the elite force of the Islamic resistance militia against Israel, Hezbollah.

Kassab was killed the day before by a drone torpedo while riding a motorcycle on a road in Tyre, in the south of the country.

The men, around the coffin, with one hand on their chest, chanted slogans that looked like prayers or prayers that looked like demands. The women, dressed in black, cried, watching the coffin pass by from the sidewalks, draped in the yellow flag of the Islamic militia.

Red poppies were thrown from the rooftops over the coffin, where children, soldiers, and military and religious leaders came to pay their respects.

And while on the other side of the border, in Gaza, the Zionist soldiers continued bombing mercilessly and in the south of Lebanon one cannot be calm, in Beirut one lives as if in a strange reality of a beautiful dilapidated city.

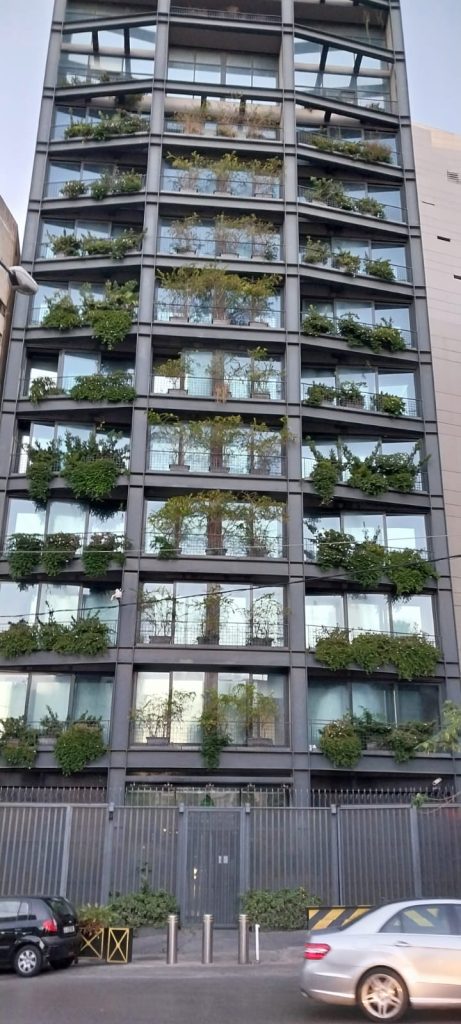

After having been the tourist and financial center of the Middle East, it preserves a surprising number of high-rise luxury apartment buildings, hotels of all categories and chic restaurants and cafes.

That same Sunday, many Beurutians enjoyed the swimming pools and spas without foreign tourists. Jewelry stores and expensive clothing stores coexist with abandoned buildings dotted with shell holes, with the absence of urban lighting and the inane government.

Barricades and tanks dot some strategic neighborhoods. The government depends absolutely on Qatar, Iran or Algeria to be able to offer minimum services such as electricity.

The Tower of Towers

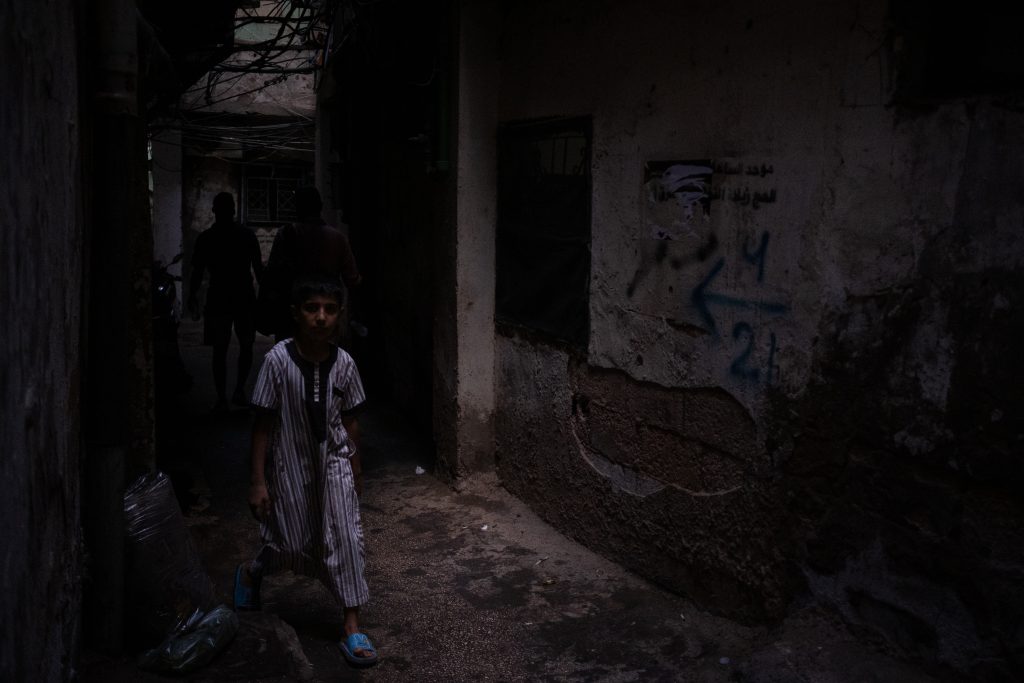

I went to visit the Burj El Baranjneh (Tower of Towers) refugee camp, which is one of the oldest and most populated in the region.

Founded in 1948 by the Red Cross to try to attend to the Nakba, it currently hosts, crammed into a space of one square kilometer, more than 20,000 refugees from Palestine and the same number from Syria.

I was devastated by the children’s reaction when they saw us: instead of asking for money like in any other impoverished part of the world, they thanked us for being there to listen to their stories and tell them to the outside world. I felt like a trickster, my levels of imposter syndrome skyrocketed, when at one point I felt a tug on my shirt behind me, I turned around, looked down and a girl of about four years old said to me with the most beautiful smile of the universe: “Thank you”.

Gazan journalists covering the Zionist genocide have become the great heroes of Palestinian childhood. More than 160 have been “martyred,” many of them with their families. Some of the survivors, like Wael Al-Dafidouh or Motaz Azaida, are the Messis of refugee boys and girls who see them as the only effective weapon they have against the injustice they suffer.

I almost died from dehydration from the sweat, but also from the tears that I kept hiding with the excuse of wiping my forehead. Before reaching the camp, at the successive entrenched checkpoints, attended with more or less zeal but always with machine guns, you must make sure that the vehicle’s music is turned off and stop it in front of any soldier who looks at the driver, who must not be wearing sunglasses and has to humbly look into the eyes of the soldier to continue circulating.

Currently, there are an estimated six million Palestinian refugees or exiles around the world who want to return to their land. In Burj El Baranjneh, 13 elderly people who arrived at the camp in 1948 still survive. In Lebanon, half a million Palestinians live poorly in 12 camps. There were fifteen of them, but three of them did not survive Israel’s regular bombing of the Lebanese Palestinian refugee camps between 1971 and 1982.

Entering the camp is like changing dimensions into a labyrinth of intricate dark alleys, due to its narrowness and the canopy of cables and pipes suspended in the air that cover the entire settlement. “There is no other place in the world like this camp,” says Jamil Abosamra, party leader and coordinator of one of the sectors of Burj El Baranjneh.

Born in Tulkarem, West Bank, he was 6 years old when in 1969 the Israeli army invaded his village for the umpteenth time. On that occasion, it was his family’s turn to say goodbye to their ancestral lands. Jamil explains that, although other refugee camps that were built later had minimal planning, Burj El Baranjneh was a vacant lot where a few families from small towns in Palestine began to arrive.

The canvas tents were transformed into wooden walls with zinc roofs. Always hoping that it would be temporary, the families began to build. “But we are surrounded. We cannot grow sideways. We had to grow upwards,” says Abosamra. The children built imprecise houses on top of their parents’ houses for five generations and today, in the Torre de Torres, there are irregular constructions of up to 14 floors.

The community leader regrets the poor help that the UN has always provided to Palestinian refugees in Lebanon: “It says it is going to do ten things and it does two. He says he is going to help 50,000 and only reaches 5,000.”

The situation of the refugees in Burj El Baranjneh, after 76 years of temporary status, remains regrettable. Many families have to share the same bathroom and privacy is at a premium.

Palestinian refugees, if they have papers, are considered third-class citizens in Lebanon. They cannot buy a house or access quality higher education or professional jobs because they are refugees.

“The Lebanese government has not always behaved well with refugees, whom they have considered terrorists in the past,” laments Abosamra, insisting on the past to avoid problems in the present.

Lebanese society not linked to movements such as Hezbollah sees the Palestinians as a problem that harms them, rather than feeling Muslim solidarity. The camp was destroyed three times in the 1980s (1982, 1985, 1988), during a civil war poisoned by Zionism with thousands dead and half of the male population imprisoned each time.

The families in the camp depend, more than on aid from international organizations, on contributions from relatives in Europe and the United States, mainly.

Abosamra has a thorn in his soul that will never be healed. Of all the hardships he has experienced in his life, there is nothing that has hurt him more than not being able to return to his town for his mother’s funeral. “It’s very hard not to be able to say goodbye,” he says sadly but convinced that he will return. “Even if I have to spend three of my remaining years imprisoned in Jordan (where he was expelled the first time), I am convinced that I will return. All Palestinians want to return, even if the UN wants to change this way of thinking,” he insists very seriously while we drink coffee and smoke in a kind of People’s House.

Our Palestinian guide, Mr Harvey, whom we called “El Niño”, took us, among other places, to the house where he was born. We went up with him to the roof, where upon seeing an active dovecote I thought I was visiting the camp’s revolutionary communications center.

It was the middle of August, it was very hot. El Niño did not want to charge us anything at all and did not allow us to pay even for the necessary bottles of water.

A “fixer” like him usually charges at least three hundred dollars to take journalists to places like this. The only thing he asked me once, with an embarrassed face, was 20 dollars to buy gigabytes for his girlfriend’s phone so he could stay glued to his cell talking with her all day long.

In the absence of infrastructure in the refugee camp, children spend their days playing in the street, running through narrow alleys and riding motorcycles without helmets years earlier than is permitted anywhere else in the world.

Karaoke

I had been sitting in the hotel room for a couple of hours in front of the computer, shocked without being able to react until Marcos called me to go to a karaoke bar in the north of Beirut where El Niño had insisted on taking us, who with his tireless 23 years it opened many doors for us.

We went Helena, the correspondent of La Vanguardia in Cairo and the most prepared, humble and supportive journalist I have ever met; Marcos Méndez, who works for several Spanish and Galician national television stations, experienced in more than fifty wars and grumpy as a teddy bear; Joan, who collaborates with more resources than she has fingers on her hands; El Niño and me.

Except for one man who sang Sinatra’s “My Way” in English, the other amateur singers did so in Arabic, with the quality of professional baritones and Mediterranean emotion.

After a dozen international adventures into which he had jumped like crazy, for the first time he had fallen into the padded terrain of the tribe of Spanish foreign correspondents in the region.

The day before I had met Manu Brabo, the Asturian photographer for an important American media, at a journalists’ dinner.

Tattooed, with rings in his ears and the body of a gladiator (although he looks puny in the photos found on Google, in person, he is impressive), the photographer, every time he opened his mouth, told an anecdote about which a movie could be filmed. . He started as an NGO collaborator in Nicaragua and started taking photos. In the Libyan Civil War in 2011 he was kidnapped by Gaddafi’s troops. In 2013 he won a Pulitzer for his coverage of the Syrian Civil War. ISIS beheaded a good friend.

Manu, very serious, sometimes with an averted gaze as if thinking that no one will understand him, has the habit of not missing a Sporting de Gijón match and to achieve this he has crossed the borders of countries at war on Sundays. He was dazed like a trapped bull, since now his newspaper does not allow him to roam freely, all his movements are monitored from New York and to leave Beirut he has to do so escorted by a security expert.

Lebanon is the only Arab country that makes wine. The ancient tradition has survived invasions and religions. It’s easy to find liquor stores open 24 hours a day and restaurants serve all types of alcoholic beverages.

I didn’t know karaoke could be so fun and exciting. We arrived scared because we had missed the highway exit and, convinced by El Niño, we drove about fifty meters in the opposite direction.

The locals, really gifted in music, reviewed their favorite songs, which I had never heard in my life, singing choruses and dancing from Arab perreo to traditional belly dancing. Tears came to the audience every time someone dared to perform a song by Umm Kulthum (1898-1975), the most beloved Egyptian singer in the entire Middle East, including the Zionists of Israel, which is known as “the greatest».

The Kulthum extended its songs for up to half an hour and more than three million people participated in its funeral procession, Helena, who speaks Arabic and knows how to dance the ardah and the dabke, told us.

Marcos supported me with alcoholic vehemence when I, a chipionero, told Helena in disgust that there is only one of the greatest, Rocío Jurado.

We lost Helena for a while because she was kidnapped to dance with a group of local women, amazed at sharing their language, rhythms and movements with a Westerner.

Marcos and I made the most embarrassing fool of ourselves singing “Me va” by Julio Iglesias.

It was four in the morning when we left karaoke. Manolito was waiting for us outside, the white Hyundai Micra rented by Marcos who has the bad habit of often greeting us with the mark of a new dent on the bodywork. Manolito brings Marcos down the street of bitterness, who despite the losses, signs up for a bombing, never better said. Finding out the countries where Marcos has worked as a war correspondent ends sooner if you ask him where he hasn’t been.

The next day I woke up with the Duolingo app to learn Arabic installed on my phone and a withdrawal-like need to listen to Saracen music.

Listening to Arabic music, whether traditional, electronic or heavy metal, I go on the transcendental journey like when I heard my first drum beats in the Caribbean.

The next day, we go to dinner at Mezyan, on the commercial and run-down Hamra street, where a DJ pairs the music perfectly with the dishes we order.

As the food dies down and the conversations rise, the music warms up. In the restaurant, like a modern luxury hotel dining room, there would be about a hundred diners, about forty of them, women from the LGBT+ community celebrating something important, or simply that it was Friday. The DJ, like the Pied Piper, took us to another dimension.

If I have never learned to dance salsa out of respect in the eyes of those watching, I do the palomo dance as soon as I listen to Lebanese music and I have drunk a couple of Almaza or Beirut, the local beers. We Westerners call the “pigeon dance” the spreading of the arms while moving the fingers of the hands while sticking out the chest, standing up and moving to the rhythm of the music.

Bombs kept raining on Gaza, but we couldn’t do anything. The border, where we must move if the situation heats up, seems cold.

However, in Beirut we did have some scares since Israel increased supersonic flights over the Lebanese capital in recent weeks. The fighters of the Zionist Army, violating Lebanese airspace with impunity, approach Beirut, descend to an altitude insanely close to the ground and, when they reach the city, deliberately break the sound barrier causing a terrifying roar of the end of the world that makes windows and doors vibrate.

These flights of psychological warfare were common in the southern region of Lebanon since Israel increased its aggression against Hezbollah last October, but in recent weeks they have also been taking place over Beirut.

Very few traffic lights work and there is only supposed to be electricity supply six hours a day, but after 50 years of shared tragedies, society has learned not to depend on the Government, which has been beheaded since 2022.

Of course, hotels and businesses have their own generators, but so do many apartment buildings.

Walking down the street in the morning you see diesel tankers unloading every few meters. Large trucks supply hotels and high-rise buildings. But there are trucks of all sizes to serve small businesses on the sidewalks, and you can even see some built by hand with welded metal sheets.

So the cuts affect the poorest and the Government more than anything. The previous weekend the airport and prisons lost power.

In Beirut you hardly see police and common crime practically does not exist. Yes, you can see soldiers stationed next to tanks and urban barricades at strategic points.

The ferries to Cyprus stopped working a long time ago and the bordering countries are the banned Syria and Israel.

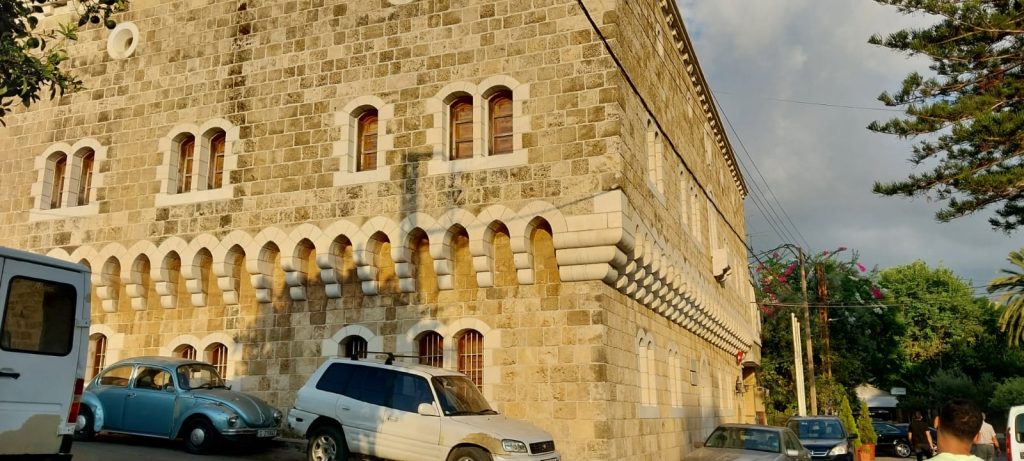

I marvel at the cedar trees that grow between buildings throughout Beirut. A cedar is the symbol that appears on the country’s flag. I have seen trinitarias as tall as cypresses adorning Phoenician, Greek, Roman and Ottoman vestiges.

There is a McDonald’s and a KFC in front of American University.

I see a town of welcoming ancient merchants, who do not deceive you too much despite the confusion with the double Lebanese dollar-pound currency, and who if they do not have what you are looking for, they call a friend on the phone and they will bring it to you.

Byblos

We decided to take advantage of the quiet Saturday to travel to Byblos, the oldest inhabited city in the world. We took the road north, Manolito, Marcos, our Generation Zeta guide, and I, ignorant, thinking that we would have to cross the desert. But Lebanon does not have a desert, it is the Arab country with the most water, and the entire coast is conurbated like Marbella or Miami.

With El Niño as DJ, we shout, more than sing, Arabic versions of “Despacito”, “La copa de la Vida” or “Bella Ciao”.

We arrived at the beach in Byblos and parked in front of an inn called Casa Pepe. We eat in a restaurant like the old beach bars of Chipiona that go into the sea on oyster stone.

After a swim, Almaza beer on the beach and a walk through the center, where if you fall you could break your forehead on a Phoenician, Greek, Roman, Persian or Ottoman cobblestone, we decided to stay the night because the war is quiet and The enclave is well worth it.

We enjoyed the city without foreign tourists. Restaurants, streets and bars are at a third of capacity. Only local tourists enjoy the wonders of Byblos in times of genocidal Zionist rage.

After a couple of Almazas on the terrace of Be La Paz, we managed to ignore our young guide, crazy about continuing on the road (“I’ll get whatever you want,” he insisted), and we go to the hotel before midnight with the intention of take a tour of the ruins the next day that we could sell as a travel report.

I didn’t sleep all night because of El Niño, with whom I had to share a room. He spent a couple of hours communicating with the girlfriend and her friends and when he went to sleep he left the music on and started snoring like a drunk giant.

At seven in the morning I went to take a shower, which was interrupted by a knock on the bedroom door. Since El Niño didn’t get up to open the door, I ran to do it myself, dripping wet and in a towel.

There was Marcos with the worried face of a bullfighter before the task: we’re leaving.

Israel attacked the Lebanese border tonight and Hezbollah launched 320 rockets. It appears to be the largest artillery exchange since 2006.

Tattoo

I did not obtain all the necessary permits to travel south that Sunday. One of the television stations he works for insisted that Marcos not take any risks. I then decided to take advantage of the time in another way. I asked El Niño if there was anyone in his refugee camp who wanted to give me a tattoo. Marcos signed up and we went with Manolito.

The young tattoo artist, El Niño’s age, asked me where I had gotten each of my tattoos. I explained to him one by one and then I confessed that for a few years I had liked to get a tattoo of something symbolic of the city or country I was writing about. He told me, without bitterness and with a smile, one of those captivating Palestinian smiles, that he would like to travel, but that, like his father, his grandfather and his great-grandfather, he could not go anywhere because of his refugee status.

With precarious means, four guys smoking around and suffering several power outages, he tattooed me the shape of a slice of watermelon, which represents the colors of the flag, with the print of the kufiyas, which symbolizes the sea, the olive trees and the land of Palestine.

When he finished he didn’t want to charge me: with that tattoo I will travel wherever you go, he snapped. Finally, he accepted me 35 dollars. I start crying every time I remember.

Fishing bombs in Marjayoun

I think I have touched all the bases of journalism, but it was not until I was fifty that I reached a war front. Now I even have a bomb to put on my resume the day I decide to get one.

To get to war you need an incalculable amount of permits, which I like to call “safe passage” because it makes me feel more authentic.

The first thing you need is a letter from the media you work for, which if they don’t know you in Lebanon your boss has to send directly in an email. Once the process has started, an official from the Ministry of Information calls you every twenty minutes to tell you that the letter has arrived, but that he is waiting for the boss to send it directly to him. I lost count of the times I answered that my boss is in Puerto Rico and that she must be sleeping at this time. I didn’t tell him that my boss was offline on vacation in Italy and that the person I was waiting for to get up was the wonderful Maribel, the one who solves everything at Claridad.

Once you have sent the letter from the media and copies of your passport (without an Israeli stamp), visa and press card, you must go to the Ministry of Information to be given the first of the safe-conduct passes. There I witnessed how a BBC team was refused permission. “But what do these people think, that because they are from the BBC they are above everything, that we have to give them everything because they are from the BBC?” the official growled.

When the six British journalists and Lebanese “fixers” left, frustrated at not having a “Moneypenny” as efficient as Maribel, the official scolded me for being late. I had gotten lost in the labyrinthine building with dark hallways where the elevators didn’t work either.

After a while verifying my papers in his office, he came out with a strange look on his face and asked me if Puerto Rico is an island, a state or what? I answered that, “sadly,” Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States. The official turned around, ran to put the appropriate stamps on my safe conduct and handed me the document with a big smile. A tear fell from my eyes. Those who know me know that I am a very tearful journalist.

After paying fifty dollars and an exchange of calls and messages, I obtained safe passage from the Lebanese Army. Every step I take I have to inform the Hezbollah liaison via WhatsApp and I always have to call somewhere else to reconfirm.

I can finally travel south, to the border with Israel.

Manolito, Marcos, the girl from La Vanguardia and I went down.

Once in the south, you have to go through an Army base in Sidon, where you have to request another safe passage from Intelligence. It was the only bad time I experienced in my two weeks in Lebanon. The Intelligence agent who was supposed to give me another code to get to the border was having a bad day. I tried to introduce myself as always, with great humility, in the language of Shakespeare.

In a Midnight Express type office, the bearded Lebanese man from Intelligence started yelling at me in perfect English: “I don’t speak English, I don’t speak French, in this country we speak Arabic, why do you come here if you don’t know how to speak Arabic?” Earth, swallow me, I thought.

“You are absolutely right, sir, I’m ashamed,” I replied, looking into his eyes while I handed him my papers.

After a long interrogation with an interpreter over the phone, I had to leave the base to make a photocopy and get a Lebanese contact phone number. Helena and Marcos were waiting for me, taking advantage of the time to tape the word PRESS on the hood of the car. After other vicissitudes that are not worth telling, always with Helena helping in Arabic, we headed towards the Lebanon border with Israel.

Marcos announced that we were entering a bombing area. I asked him if identifying Manolito as a press vehicle wouldn’t be counterproductive, given how the Zionists, just a stone’s throw away there, like to kill journalists. He shrugged.

We spent two hours at a checkpoint because they still hadn’t given me the OK, despite having all the safe conduct permits. The girl from La Vanguardia, who is in her twenties and knows much more about everything than I do and often called Marcos and me boomers, spent the two hours fighting on the phone in Arabic and English with officials from half of Lebanon to get me they will let pass.

In a moment of boredom, I asked Marcos, furtively pointing with his head at the tank on one side of the checkpoint, the cannon on the other, and the soldiers’ machine guns, if he knew how to identify the weapons.

He answered me with gibberish that mixed Russian AK-47s with Azerbaijani submachine guns, implying that he had no idea.

What a shitty war correspondent you are, I told him with a silent look that I think he understood because first he put on his grumpy Smurf face and then we laughed together.

Then Helena intervened, abandoning her efforts for a second to let me pass: I took a blablabla course with an expert who taught us mimi mimi mimi mimi.

The girl from La Vanguardia, who has already covered even the war in Ukraine, managed to let me pass.

We arrived in Marjayoun, at the house of the “fixer” Nuhad and her husband, Lotfallah Daher, a man who has been documenting Israel’s attacks on the Lebanese border from the roof of his house for forty years.

The roof is covered with solar panels so as not to be left without connection, there is a booth with everything you need to follow the news and broadcast, and in the afternoons they welcome their friends to spend time drinking coffee and watching bombs fall.

As if it were the most normal thing in the world and laughing, Nuhad and Lotfallah tell how the previous Sunday, while we were sleeping in Byblos, the most intense exchange of fire since 2006 occurred.

“In two hours more bombs fell than in months. Sometimes three explosions every second. It started at five, just before dawn. Our grandchildren, who live downstairs, with their eyes closed from sleep, asked why there was so much light,” explains Nuhad.

Marjayoun is a town one kilometer from the border where about eight thousand people lived. Now there are about a thousand left. From the roof you can see another town, rebuilt several times and which has now been completely evacuated.

In Marjayoun there is a Spanish United Nations base, that’s why there is a Bar Pablo and Lotfallah puts on a red cap to talk to us.

“The Spanish protect us. They don’t do anything, but they protect us,” laughs Lotfallah, who makes a joke out of any drama. He explains that in the 2006 war five Spanish soldiers died in an explosion. It shows us the exact point. The Spanish military, since then, cannot leave the base except in a convoy, which does not stop in the town, so that community has lost a lot of income.

From the rooftop of Nuhad and Lotfallah you can see part of the ten kilometers of Israeli wall in the area. Lebanon’s border with Israel extends 145 kilometers of wall or electrified wire.

The territory where Nuhad and Lotfallah live was invaded for 10 years by Palestine, then 25 years by Israel and now by Iran, says the native photojournalist, referring to Hezbollah’s control. “There is no Lebanese government here,” says Lotfallah, who believes a deal between Israel and Hezbollah will happen soon. “This is the beginning of the end,” he hopes.

The bomb photographer is not happy with the control of “the yellows.” He assures that «since Hezbollah arrived, the economy and our happiness have ended» and that every time something bad happens and it is not known who it was, «it was Hezbollah.» He assures that, since October 7 of last year, Hezbollah «controls everything in Lebanon, including the government.»

Lotfallah boasts of knowing how to identify any sound to differentiate it from bombs.

“I can assure you if what we heard was a truck crashing or if it was a red or blue Jeep backfiring,” he joked.

I had my eyes focused on my notebook as I wrote down what Lotfallah was telling me when a loud bang sounded. I finished writing the sentence and when I looked up, Helena, Marcos, Nuhad and Lotfallah were already standing at the edge of the roof, pointing their phones and cameras at the border wall as if they were holding fishing rods that had been bitten.

We caught a bomb that fell a few kilometers away, very close to the Israeli wall. We could not capture the moment of impact, but we could capture the terrifying column of smoke.

Marcos, that man who knows horror first-hand and whose heart still breaks when he sees someone suffering, looked at me as if showing off: let’s see who takes you to these places.

The farewell

I felt very good despite being a witness to the greatest infamy. You could say that journalists live off the misfortunes of others. But if we are not there, who is going to tell them?

When you tell your colleagues that you managed to travel south and that a bomb fell near us, they say: “How cool.” My last night in Beirut was also that of the girl from La Vanguardia, who returned to Cairo the next morning. We made jokes about how cool it would be if they bombed the airport, without casualties, of course, so that we couldn’t leave and would have to stay longer in Lebanon.

Something similar happened to Joan, the 31-year-old Catalan who has been in the country for five years and who only misses a party if he has to do a live TV report at the same time.

Joan arrived in Lebanon for three months to do an internship. When he finished, he gave himself two weeks to find a life as a journalist. Then “the revolution happened, which helped me get a foot in the journalistic market. And from there, everything exploded: the revolution, the repression, the failed economy, the covid, the port explosion, the war with Israel… It was me arriving and shaking the world.»

Joan is a welcoming guy who enjoys his life with as much intensity as he does, empathetically and supportively, that of his colleagues, whether they are permanent workers or parachutists.

For my part, I was overjoyed, I had managed to write, falling by parachute, without knowing the country, five decent chronicles in two weeks.

It is not easy to describe the daily life of the people of Lebanon. The country’s distant and recent past has chiseled the urban appearance of Beirut, where the surprising mix of large hotels and super-luxury apartment buildings with abandoned buildings, and monuments and even palm trees riddled by impacts from high-caliber projectiles. Colonial and modernist style buildings remain from the time of the French mandate in the region (1918-1948); the street signs, which say Rua; the Lebanese pound banknotes, which are in Arabic and French; and that around 20 percent of the population speaks French regularly.

About thirty casinos have survived the wars, such as the Monegasque Casino du Liban, which opened in 1959, closed in 1989 and reopened after a reconstruction in 1996. Dining on one of its terraces gives the impression that in James Bond will appear any moment.

Some streets are bustling with people doing their thing, with shops where a person works and his friends smoke hooka on the sidewalk; with women who drive all types of vehicles, smoke, and some even make eye contact, hold their gaze and smile.

The Lebanese have learned to escape hardship with a syrup of frivolity.

And, as the song «School of Heat» by Radio Futura says, and despite Lebanon being a country in war or permanent crisis since 1975, “in the private pools, the girls bare their bodies in the sun.” ie